I don’t much care for the pledge of allegiance. This got me into a bit of hot water when I was the convocation speaker at Hillsdale College, standing on the stage right next to the flag, silent and polite, while the assembled faculty and studentry recited the pledge.

Don’t get me wrong. I love the “standard to which the wise and honest can repair.” And I confess I’ve gotten misty-eyed when I’ve seen Old Glory flown around a rodeo arena, as the sun is setting over the Rocky Mountains.

Alas, the pledge of allegiance had an ugly midwife: the Christian Socialist Francis Bellamy, who was kicked out of his Boston pulpit for preaching against the evils of capitalism. Not for me, the pledge to a symbol or the Hegelian nation. And not for me a pledge that was accompanied by the Bellamy salute, until it was quietly dropped during World War II because it looked a little too much like Nazi theatrics.

The pledge was a clever work of Progressivism. It inculcated allegiance to the state and the abstract patria, while ignoring the bedrock of American liberty, the US Constitution — because its pesky constraints might otherwise thwart wise leaders who can fix all of our problems with the stroke of a regulatory or legislative pen.

I am, however, ready to pledge allegiance to the Constitution.

In fact, back in 1996, I did “solemnly swear that I will support and defend the US Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” I was an eager 23-year-old Foreign Service Officer, taking my oath of office. I left the Foreign Service because the State Department opened my eyes to the ills of bureaucracy, and because too many of my colleagues were not defending the Constitution. Ironically, the US Government made a libertarian of me.

What’s so special, so laudable, so lovable about the US Constitution?

The Constitutional Contract

The economist James M. Buchanan (Nobel Laureate, 1986) founded the discipline of constitutional political economy. In the simplest of terms, he explained how a constitution might emerge out of a state of nature. My neighbor and I live in a constant state of fear, as we routinely raid each other. Instead of dedicating resources to innovation and capital accumulation, we dedicate resources to defense (and offense). One day, we realize this doesn’t make sense. Instead of eking out a living in constant fear of plunder, we could agree to live in peace, divide labor according to comparative advantage, innovate, accumulate capital — and, generally, both become rich.

There remain two problems. First, each party will cheat on the contract if it thinks it can get away with it. So we need an outside enforcement mechanism. But this leads to a second problem: how do we control that entity? Neither party will sign off on the constitution if there aren’t explicit conditions for contractual enforcement — especially if the other party could someday be in power. In the powerful language of Federalist 51: “In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”

The [Expanded] United States Constitution

I like to read the Constitution as a three-part document: the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of 1787, and Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. This establishes the Constitution as the institutional fulfillment of a philosophical statement, and one that is still growing into its promise. Fellow nerds will complain that there are more than three documents… touché! A fuller understanding requires a reading of earlier philosophy (Locke, Montesquieu, Milton, and others); the Federalist Papers; the Articles of Confederation; and the Constitution of the Confederate States (though it was born of grievous sin, it did address a century of constitutional learning, and addressed both federal overreach and a scandalously latitudinarian reading of the Commerce Clause). But let’s start with the starring three.

The Declaration of Independence submits a list of colonial grievances against the British Crown. A contemporary reading that substitutes “president” or “federal government” for the British Crown will show the perennial nature of governmental overreach. But the core is contained in the beginning: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” From a pithy statement of metaphysics, epistemology, and ethics, flows a simple political theory: “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…”

The Constitution is the institutional implementation of the Declaration’s philosophy. Back to Federalist 51, the Constitution enables the federal government to “establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” It does so through such things as unified foreign policy and defense powers, the regulation of commerce between the states, the ability to call forth the militia to quell insurrections, and the Supremacy Clause (Article VI) over the states. The Constitution also “oblige[s] [the federal government] to control itself.” This, it does through separation of powers (“ambition [is] made to counteract ambition”); through a balance of power between the states and the federal government; and through the granting of limited and enumerated powers to the federal government (notably under Article I, Section 8, and the Tenth Amendment). To these measures, we can add the Bill of Rights and the Reconstruction Amendments.

Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech completes the trifecta. Indeed, a major line of dissent against the Constitution (embodied in identity politics and the debunked 1619 Project) seeks to recast the American founding as a simplistic story of racism. Of course, the Constitution did not immediately actualize the vision of the Declaration of Independence. But consider the history: before the Enlightenment, nobody (except for a handful of nobles and bishops) had rights, and everybody was poor. Then something — something radical — changed: some people in some countries saw their rights recognized. Not everybody, not everywhere, not immediately. But increasing numbers of people in increasing numbers of countries came to be included in the Enlightenment fold, and prospered accordingly. That project is still unfolding. Rather than throwing out the proverbial constitutional baby with the bathwater, and dumping the Enlightenment project because it wasn’t immediate or perfect, we are called to expand it.

Consider the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s speech:

When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us, upon demand, the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

Is The Constitution Still Relevant?

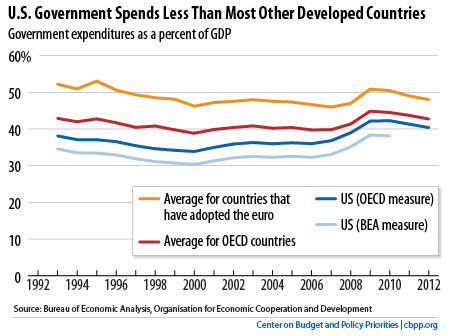

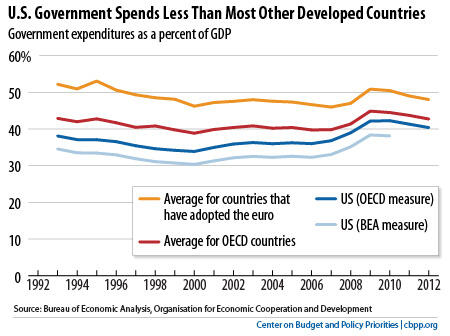

Critics have argued that the Constitution of 1787 went too far in empowering (versus constraining) the federal government. In hindsight, perhaps the Anti-Federalists were right, as the federal government has grown from its small scope of enumerated powers, into a behemoth that controls a third of the economy. The Constitution has been ignored and bypassed, as federal growth has been enabled by the Supreme Court. But a weaker confederation would surely have been abused also. And for all its shortcomings, the US Constitution remains a speedbump on the road to serfdom. The US is consistently within the top ten (and usually within the top five) most economically free countries. It is among the lowest public spenders within the OECD.

The United States remains a solid democracy. It may be a dirty shirt, but it’s the world’s cleanest dirty shirt. In the words of Algernon Sidney’s epigraph to Hayek’s The Constitution of Liberty:

Our inquiry is not after that which is perfect, well knowing that no such thing is found among men; but we seek that human Constitution which is attended with the least, or the most pardonable inconveniences.

Other naysayers have claimed that the Constitution represents an unfair claim of the past on the present. The “organicists,” for example, claim that the Constitution is a living document and subject to pragmatic reinterpretation, without the need for amendment. But if a constitution can be interpreted at the drop of a judicial hat or legislative act, it means nothing — and it fails at its fundamental purpose of constraint.

What is more, the Constitution can be amended, whether for clarification, or to reflect the changing times (for example, ending slavery, recognizing women’s right to vote, or changing the voting age to eighteen).

So, the Constitution is not sacred because it is inalterable, or because it is old. It is sacred because it represents voluntary self-constraint. It treats power as dangerous, and assumes that even the well-intentioned will eventually abuse it. We are still tempted by shortcuts, still eager to trade liberty for promises of security. The American experiment survives only when citizens insist that government stay within its bounds — especially when doing so is inconvenient.

So yes: I will pledge allegiance to the Constitution — and I hope you will, too. An enduring constitution requires a public that understands it, a judiciary that respects it, and leaders who fear violating it more than they fear losing elections. It survives only when citizens refuse to let it be hollowed out by “emergencies,” reinterpreted into meaninglessness, or bypassed by administrative decree.

That kind of humility is all too rare in modern politics, and it is well worth defending.