While most of my fellow Michiganders like to think of Detroit as the birthplace of the automobile, we have to remember, the Germans have us beat.

German inventor and entrepreneur, Carl Benz submitted his patent application on January 29, 1886, and as car buffs know, this represented the advent of the world’s first production automobile, the Motorwagen. The story goes that its maiden roadtrip was taken by Benz’s wife, Bertha and their two sons, Eugen and Richard, supposedly without letting the inventor know! That Model #3 topped out at two-horsepower and a blistering 10 miles per hour. Despite its humble specs, Bertha took it out on an arduous 121-mile route now named in her honor, running from Mannheim to Pforzheim and back.

The lore surrounding the Motorwagen’s origins have become settled auto history. Less clear, strangely, is the original sales price. Reported estimates put the price tag at anywhere from $150 (600 German marks) to $1,000. As one would imagine, even the lower price point would have been a hefty purchase for the average German at that time, with an estimated annual income per person between 400 to 500 marks. For some years, the purchase of an automobile would remain a luxury, reserved for the upper crust of society in both Europe and the US. That is, until the rise of the Ford Motor Company’s Model T in 1908.

While there were other innovators in the automotive industry, Henry Ford’s vision transformed the car from a luxury to a possibility to a necessity in the US. His stated aim was to:

build a motor car for the great multitude…constructed of the best materials, by the best men to be hired, after the simplest designs that modern engineering can devise…so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one – and enjoy with his family the blessing of hours of pleasure in God’s great open spaces.

All Michigan youth are infused with great pride for the state’s auto industry, steeped in its shared history and folklore. We were all told the story that Ford would famously sell the Model T in any color the customer wanted, “as long as it’s black.” During that age of simple efficiency, Ford produced over 260,000 of them in 1914, with many more to come. In the same year, the sticker price, according to the Model T aficionados, was $500 for the Roadster, and $750 for the Towncar. These prices would continue to decline (post-WWI inflation aside) to a 1925 low of $260 for the Roadster and $660 for the souped-up “Fordor” model.

To provide further perspective, the per capita personal income of Michigan residents (when first measured just four years later) was $792 per year. Approximately 650 hours of labor were traded to purchase the base Model T. How does that stack up against today’s labor cost for a base model vehicle?

For the sake of comparison, let’s take the Ford Maverick, which in many ways is a modern analog to the Model T. Both are capable of mild off-roading and are marketed to the “everyman,” with reasonable hauling capacity and sufficient comfort for an extended road trip. The Maverick’s MSRP of $29,840 for the base model (the SuperCrew XL) takes significantly more labor hours than its predecessor in the 1920s. With an estimated per capita personal income for 2025 of $63,620 (an average wage around $31.80 per hour), the Maverick would require nearly 940 hours to purchase. After financing the purchase (as most Americans do) the final price could be over $39,000, the equivalent of 1,235 labor hours.

Setting aside the simpler, utilitarian Maverick, it’s been widely reported that the average price of a new vehicle in the US has crept north of $50,300. For residents of the Great Lakes State, that equates to 1,581 labor hours. Financed under average terms ($10,000 down, seven percent interest for 60 months), the total cost is nearly $64,500, or 2,028 labor hours, the equivalent of an entire year’s work. Of course, in an economy that is relatively freer than many others, even the cheapest new car available in America right now, the Kia K4, would chew up 740 labor hours at a $23,535 sticker price. That’s still 90 hours more for the average worker for the absolute cheapest model than it was in Ford’s day. Midwestern work ethic aside, this is a tough row to hoe.

Quality improvements are important to consider — there’s no knowing what even an entry-level modern car would’ve sold for in 1925. But over the same period, competitive forces and global efficiencies have brought down the cost of many car components. The cost of financing is another reasonable objection to this comparison — the average annual budget burden isn’t so bad, even though the total paid is higher. Installment and credit purchase plans, which Henry Ford personally regarded as morally repugnant, were already available in the 1920s. In fact, the company resisted, but lost significant market share during the roaring ‘20s when competitors like General Motors deployed credit purchasing. As a result, in 1918 roughly half of the cars on US roads were Fords, but by 1930, 75 percent of US-owned vehicles were purchased on credit — from other manufacturers. Ford relented, opening its own financing arm.

These early outcomes portended the use of expansionary credit creation by commercial banks (under the permissive interventions of the Federal Reserve) have boosted demand beyond what it would otherwise be. Because of the availability and widespread use of debt to obtain new vehicles, overall demand, and inflation-adjusted prices have risen significantly. At the advent of debt-based car financing, they could be bought with fewer than one-third of the average worker’s time on the job. Over the twentieth century, and because of the ongoing growth of the credit market for car purchases, they’ve been subjected to a long, slow-burning price inflation. An increased share of US workers’ paychecks and hours are spent on both new and used vehicles.

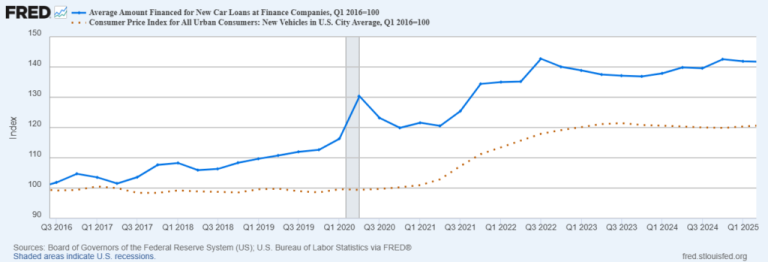

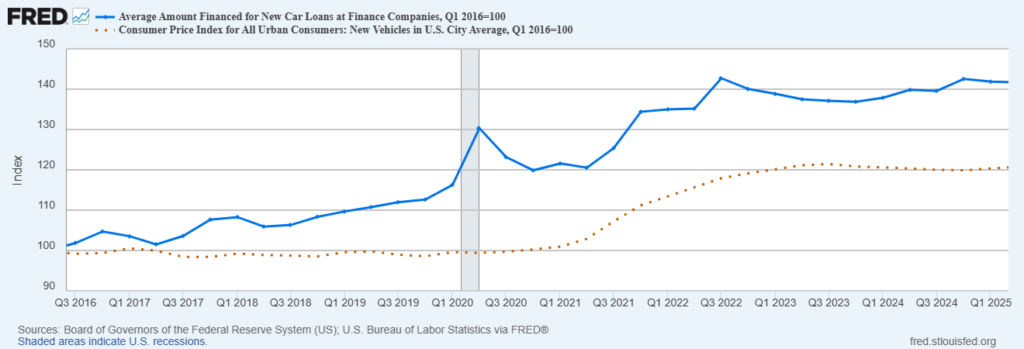

The most recent data on the relationship between credit expansion for new vehicles and their prices show that increases in credit offered on new cars lept by 30 percent from 2016 through Q2 of 2020, while the CPI for new vehicles hadn’t budged. It wasn’t until Q2 of 2021 that prices began to rise, reaching a 20 percent increase vs 2016 prices in Q1 of 2023. What explains this outcome?

A brief statistical analysis of the data displayed below, shows that a 10 percent increase in the average total financed for cars since 2016 is associated with a 7 percent increase in prices one year later. If this story sounds familiar, it’s the same pattern that emerged in higher education markets. In the early 1990s, an expanded student loan program contributed to tuition price surges, and many of those loans are being paid off until this very day. Of course, credit expansion isn’t the only thing that drives prices higher in later stages, but it does appear to play a role alongside other factors.

While credit expansion impacts demand and drives prices higher with a delayed transmission, what else has contributed to the affordability problem? To be sure, the administrative state and its massive burdens bear significant responsibility for diminished affordability. Regulatory requirements, including safety, emissions, and fuel economy standards, are estimated to account for roughly one-eighth to one-fifth (about 12.5 percent to 20 percent) of the total price of a new vehicle. That’s not to mention mandated backup cams, kill switches, emissions converters, and others, all driving up the price of a minimum model.

There is some positive momentum in addressing vehicle affordability, but remains a hot topic in our current political and economic discourse. Recently, headway has been made in the deregulation of the auto industry. Revisions to Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards were touted by Secretary Duffy at the Detroit Auto Show. He praised the changes as a pathway to increased American automotive productivity and lower costs for buyers.

Whatever regulatory burdens are lifted, change won’t happen overnight. The auto industry must retool, re-engineer, and bring to market the next models. Further, a return to sound monetary policy and competition in money production, with less reckless lending practices are needed for an easing of the price pressure in the car and light truck market. Only coming years will tell whether car affordability will return to what it was under Henry Ford.